Coronary Anatomy and Blood Flow

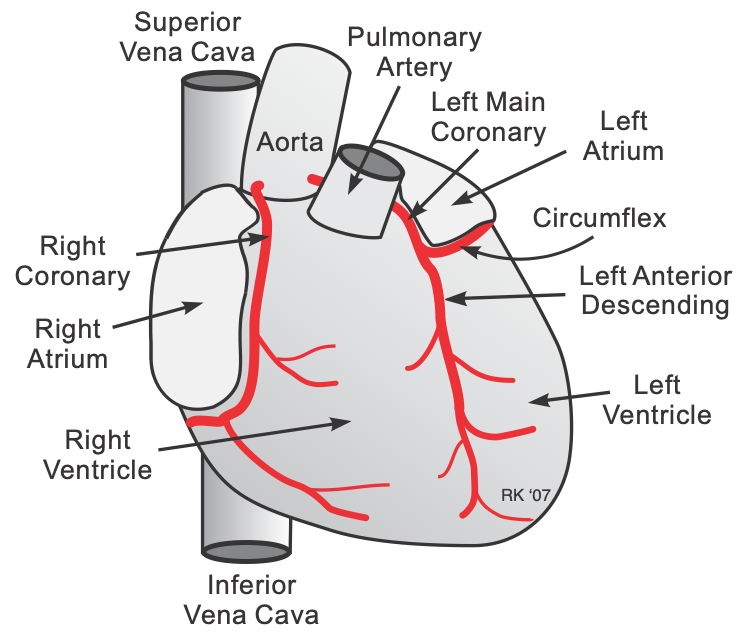

The major vessels of the coronary circulation are the left main coronary that divides into left anterior descending and circumflex branches, and the right main coronary artery. The left and right coronary arteries originate at the base of the aorta from openings called the coronary ostia, behind the aortic valve leaflets.

The major vessels of the coronary circulation are the left main coronary that divides into left anterior descending and circumflex branches, and the right main coronary artery. The left and right coronary arteries originate at the base of the aorta from openings called the coronary ostia, behind the aortic valve leaflets.

The left and right coronary arteries and their branches lie on the surface of the heart and, therefore, are sometimes referred to as the epicardial coronary vessels. These vessels distribute blood flow to different regions of the heart muscle. When the vessels are not diseased, they have a low vascular resistance relative to their more distal and smaller branches that comprise the microvascular network. As in all vascular beds, it is the small arteries and arterioles in the microcirculation that are the primary sites of vascular resistance, and therefore the primary site for regulation of blood flow. The arterioles branch into many capillaries that lie next to the cardiac myocytes. A high capillary-to-cardiomyocyte ratio and short diffusion distances ensure adequate oxygen delivery to the myocytes and removal of metabolic waste products from the cells (e.g., CO2 and H+). Capillary blood flow enters venules that join to form cardiac veins that drain into the coronary sinus on the posterior side of the heart, which drains into the right atrium. There are also anterior cardiac veins and Thebesian veins drain directly into the cardiac chambers.

Although there is considerable heterogeneity among people, the following table shows the regions of the heart that are supplied by the different coronary arteries. This anatomic distribution is important because these cardiac regions are assessed by 12-lead ECGs to help localize ischemic or infarcted regions, which can be loosely correlated with specific coronary vessels. However, because of vessel heterogeneity among patients, actual vessel involvement in ischemic conditions needs to be verified by coronary angiograms or other imaging techniques.

| Anatomic Region of Heart | Coronary Artery (most likely associated) |

| Inferior | Right coronary |

| Anteroseptal | Left anterior descending |

| Anteroapical | Left anterior descending (distal) |

| Anterolateral | Circumflex |

| Posterior | Right coronary artery |

The following summarizes important features of coronary blood flow:

Flow is tightly coupled to oxygen demand. This is necessary because the heart has a very high basal oxygen consumption (8-10 ml O2/min/100g) and the highest A-VO2 difference of a major organ (10-13 ml/100 ml). In non-diseased coronary vessels, whenever cardiac activity and oxygen consumption increases, there is an increase in coronary blood flow (active hyperemia) that is nearly proportionate to the increase in oxygen consumption.

Good autoregulation between 60 and 200 mmHg perfusion pressure helps to maintain normal coronary blood flow whenever coronary perfusion pressure changes because of changes in aortic pressure.

Adenosine is an important mediator of active hyperemia and autoregulation. It serves as a metabolic coupler between oxygen consumption and coronary blood flow. Nitric oxide is also an important regulator of coronary blood flow.

Activation of sympathetic nerves innervating the coronary vasculature causes only transient vasoconstriction mediated by α1-adrenoceptors. This brief (and small) vasoconstrictor response is followed by vasodilation caused by enhanced production of vasodilator metabolites (active hyperemia) due to increased mechanical and metabolic activity of the heart resulting from β1-adrenoceptor activation of the myocardium. Therefore, sympathetic activation to the heart results in coronary vasodilation and increased coronary flow due to increased metabolic activity (increased heart rate, contractility) despite direct vasoconstrictor effects of sympathetic activation on the coronaries. This is termed "functional sympatholysis."

Parasympathetic stimulation of the heart (i.e., vagal nerve activation) elicits modest coronary vasodilation (because of the direct effects of released acetylcholine on the coronaries). However, if parasympathetic activation of the heart results in a significant decrease in myocardial oxygen demand because of a reduction in heart rate, then intrinsic metabolic mechanisms will increase coronary vascular resistance by constricting the vessels.

Progressive ischemic coronary artery disease results in the growth of new vessels (termed angiogenesis) and collateralization within the myocardium. Collateralization increases myocardial blood supply by increasing the number of parallel vessels, reducing vascular resistance within the myocardium.

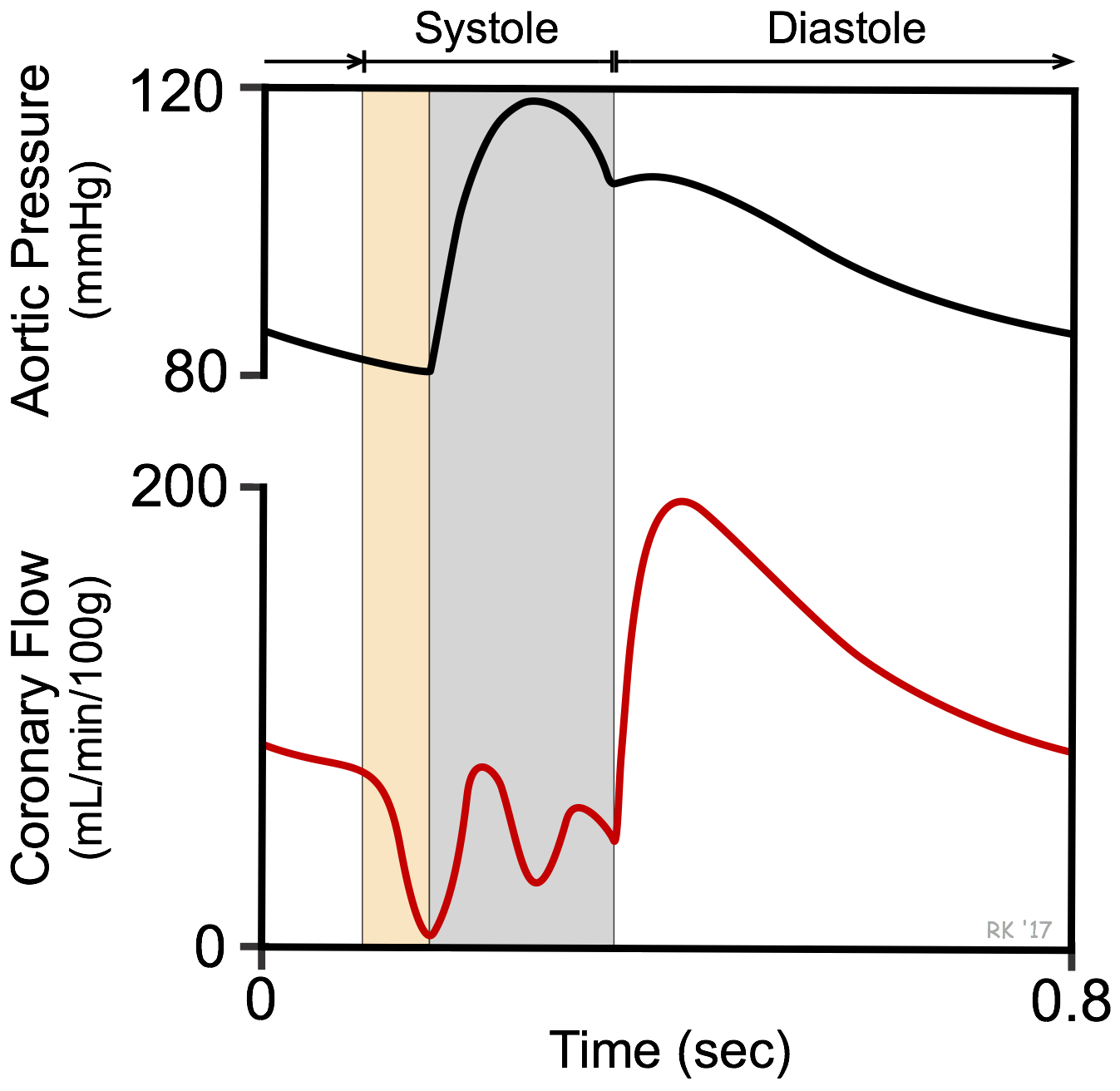

Extravascular compression (see figure) during systole markedly affects coronary flow.

Therefore, most of the coronary flow occurs during diastole. Because of extravascular compression, the endocardium is more susceptible to ischemia, especially at lower perfusion pressures. With tachycardia, there is relatively less time available for coronary flow during diastole to occur – this is significant in patients with coronary artery disease, where coronary flow reserve (maximal flow capacity) is reduced.

Therefore, most of the coronary flow occurs during diastole. Because of extravascular compression, the endocardium is more susceptible to ischemia, especially at lower perfusion pressures. With tachycardia, there is relatively less time available for coronary flow during diastole to occur – this is significant in patients with coronary artery disease, where coronary flow reserve (maximal flow capacity) is reduced.

In the presence of coronary artery disease, coronary blood flow may be reduced. This will increase oxygen extraction from the coronary blood and decrease the venous oxygen content. This leads to tissue hypoxia and angina. If the lack of blood flow is because of a fixed stenotic lesion in the coronary artery (because of atherosclerosis), blood flow can be improved within that vessel by 1) placing a stent within the vessel to expand the lumen, 2) using an intracoronary angioplasty balloon to stretch the vessel open, or 3) bypassing the diseased vessel with a vascular graft. If the insufficient blood flow is caused by a blood clot (thrombosis), a thrombolytic drug that dissolves clots may be administered. Antiplatelet drugs and aspirin are commonly used to prevent the reoccurrence of clots. If the reduced flow is because of coronary vasospasm, then coronary vasodilators can be given (e.g., nitrodilators, calcium-channel blockers) to reverse and prevent vasospasm.

Revised 11/03/2023

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021)

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021) Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)

Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)